Re-thinking legal aid applications

How I helped a team at the Ministry of Justice build the right thing and understand its users.

As a result of this work:

user satisfaction increased from 34% to 100% (in the first 3 months)

solicitor time to complete the form reduced from ‘hours’ to 18 minutes

a more trusting relationship started to emerge between the agency and its users

“We are very happy with the new process. It takes 15 minutes, it took up to an hour previously depending on the case”

What was asked for

I joined the team tasked with transforming the application for legal aid assessment. I was on the team for 18 months during the alpha and private beta phases.

I was brought in to lead, organise and execute a programme of qualitative and quantitative research.

I ended up having a much broader impact, touching on many areas of product, from value proposition to accessibility.

The context

Legal aid is a £1.7 billion government fund that allows people who cannot afford it get legal representation. It is a crucial part of a fair and just society helping up to 500,000 people a year (at the time of this work) get their lives back on track.

Approximately 3,700 legal firms get contracts with the Legal Aid Agency (LAA, part of the Ministry of Justice) to offer applicants in England and Wales legal protection and representation.

Solicitors consider applicants’ financial eligibility and case strength. Then they apply for funding to represent applicants in legal proceedings. These applications are processed by caseworkers who decide whether or not to grant the funding.

Legal aid cases range from civil matters, such as child protection and family mediation, housing and immigration, to criminal.

The suitcase one solicitor used to carry paperwork to court

Catalyst for change

Significant cuts to legal aid were introduced in 2012-2013.

This trebled the number of people going to court without representation and caused closure of many legal centres offering legal aid, causing a 59% decline (according to the the Law Society).

It was becoming unsustainable for solicitors to use the incumbent application system as it took too long and caused them to lose data. Caseworkers faced similar issues.

The poorly working service added to the tensed relationship between solicitors and the agency, causing misunderstanding and suspicion.

What I did

Some of the things I did:

reviewed and surfaced past work

observed and interviewed applicants, solicitors and case workers in their context up and down the country

ran empathy workshops to immerse the team in real financial evidence and case details

mapped outcomes to impact

facilitated consequence scanning workshop

maintained a live accessibility and inclusive design tracker, conducted accessibility reviews with assistive technologies and used inclusive participant sample

“Vero quickly became an integral and highly respected member of our product team and her work and approach led us to release a more valuable product.

— Alice Cudmore, Product manager on the team

Challenges we faced

Pressure to pursue a certain technology

The business case for our team rested upon delivering savings through automation. Most prominently, the team had to automate bank statement entry to save solicitor and caseworker time.

The team was excited to become the first public service to do so.

Open banking was supposed to allow applicants to grant access directly to their bank accounts, avoiding the need for paper statement processing.

Culture of mistrust and suspicion

In the post-cut climate trust between the legal aid agency and the providers was low.

When we visited solicitor offices in some of the most deprived areas, we realised that the internal perspective was shaped by myths or exceptions.

Speaking to caseworkers, we also realised that they were making decisions within the confines of rules and policies that life did not always fit into.

Our challenge was to bring this understanding back to the agency and show that we needed to dispel myths on both side.

Applicants’ realities were complex and messy

The applicants who experienced domestic abuse (the area we focused on) often fled their homes to stay in temporary housing.

Their bank accounts were often controlled by their abusers. They had low trust in the ‘government’. Many lacked the technical skills and relied on cash payments.

“Clients seeking help have finances in state of flux and brains in state of flux. Often they were turning up with little or no paperwork.“

— Solicitor

The made up data we were using in our prototypes prevented us from seeing how difficult the designs would be to use with real data.

While a good idea on surface, research was showing that ‘open banking’ would not work for the messy and difficult realities of many, if not most, of the applicants.

The impact I had

I’m most proud of defining an alternative product strategy, building accessibility in from the start and helping build trust through empathy.

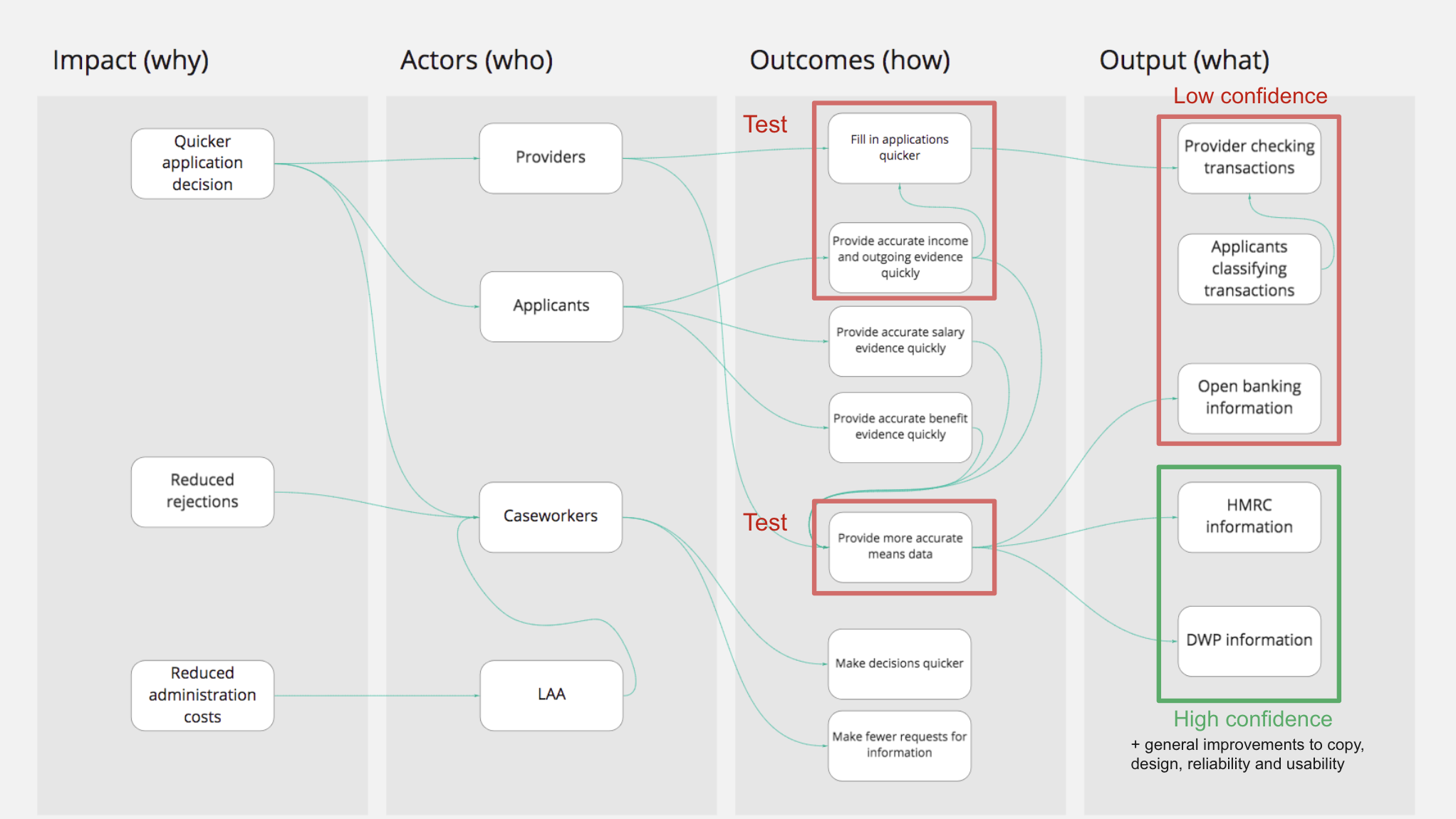

Impact map that I created and used as a basis for testing hypotheses

Facilitated a team pivot

The team was under pressure to deliver savings through automation tied to ‘open banking’. However, signals from the various user research activities pointed to this not delivering the value we were hoping for.

I instrumented a team pivot through:

agreeing testable hypotheses with the team and running several rounds of observation and interviews to test those

gathering data (ease of use, speed and trust)

offering an elegant and simple alternative allowed us to deliver value almost immediately, while keeping the ‘open banking’ solution as a later potential optimisation option

Re-framing the narrative like this made the team see a path to success and armed them with rationale to take to senior leadership.

As a result we made some design changes:

returned the applicant part of the journey to solicitors who were already used to filling it in

focused on a simpler (‘passported’), high-volume journey - reducing the development effort needed before private beta launch

launched the simpler private beta journey and started work to augment it

This put the team in a great place to meet providers’ needs, so they could, in turn, meet applicants’ needs, helping them find safety.

Re-building trust

The launch of private beta service was a turning point in the trust between providers and the agency. The service allowed them to focus on helping applicants, not “oodles of paperwork”.

Leading up to this moment were hours of user research activities in which I involved designers, product managers, the wider team.

Caseworkers started to see that solicitors were driven by the same goal.

Towards the end of my time on the team, we started engaging policy colleagues and raising with them issues that required policy attention, such as financial evidence for the self-employed clients.

“Caseworkers would ring you up and you’d have a relationship, now this system is working back towards rebuilding that trust”

— Solicitor

“This is incredible, don’t need to worry about cost limitations. That worry has kind of gone, we have room to move without having to make amendments”

— Paralegal

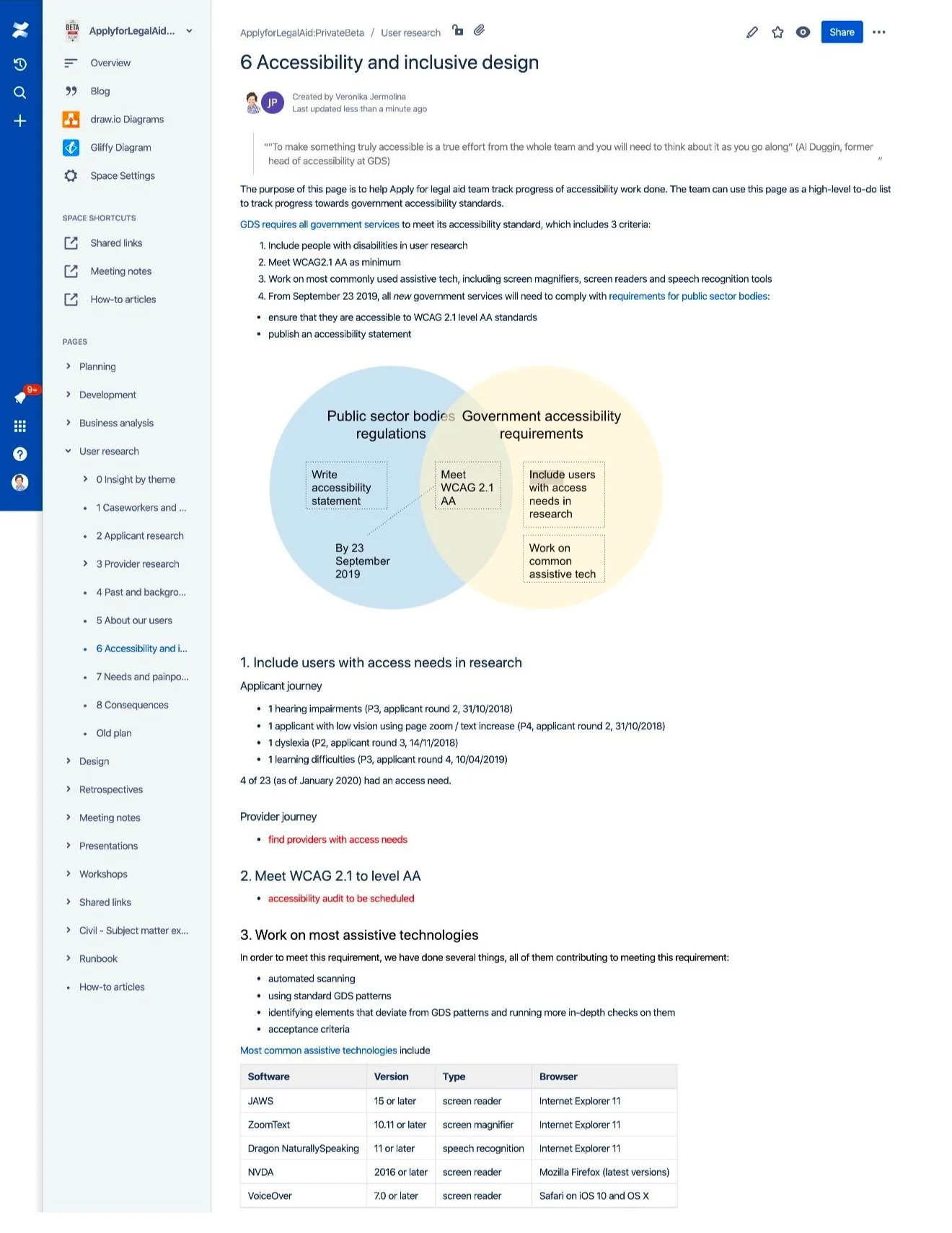

Building accessibility in

I drove the team’s accessibility efforts from the beginning, also known as ‘shifting left’. Some of the things that I did:

inclusive research - 17% of research participants had an access need

collaborated with developers to add automatic accessibility checks

conducted ad-hoc testing with assistive technologies

documented any non-standard patterns used

maintained an up-to-date page of all accessibility work done

This allowed the team to be a good place to meet accessibility standards and the needs of disabled users.

This approach helped save money as it was effectively ‘free’, compared to expensive retrospective fixes.

Reflection

The team’s focus on shiny new technology was well-intentioned but left us stuck in a build trap. We risked failing the very people we set out to help and missing the opportunity to build a better relationship.

By facilitating the mapping of outcomes to impact, focusing on data and envisioning alternative viable options, I helped the team step back and re-focus their efforts toward success.

If you are facing a similar challenge, let’s talk.