Delivering the government’s crisis response for education

How user research shaped strategy and policy during the Department for Education’s emergency rollout of 1.3 million devices to schools in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Image credit: School Week

As a result of this work:

1.3 million children received a device to continue remote education

taxpayer money was saved by more effective iterative user-centred policy design

the service passed its GDS assessment

“I hope that you appreciate the considerable impact you have had on the education of our children at one of the most challenging periods in our nation’s recent history.”

In March 2020, when the global COVID-19 pandemic hit, I was working at the Department for Education (DfE).

As England’s 24,000 schools closed, a crisis response programme was created to deliver devices and connectivity to schools so children could continue learning.

We had to quickly understand what schools and families needed to continue online learning. We then had to source and deliver the necessary technology, against a backdrop of global scarcity, border closures and movement restrictions.

Rows of laptops being set up in a warehouse. Image source: DfE, edited with ChatGPT

My role and impact

I led user research on several teams and collaborated with and mentored other researchers on the programme.

Strategic research

My work informed the programme’s strategic direction in the early rollout, as well as when the programme shifted focus from quantity to quality after meeting initial targets.

Research methods and interventions

I applied and adapted a mix of methods and frameworks, including:

internal workshops to create design principles that acted as a north star for teams

semi-structured interviews, Zendesk ticket analysis and tree testing to expose information architecture gaps causing support queries, illustrated the findings in a journey map and worked with content designers to design fixes

leading research and iteration for a smooth extension of the programme to further education

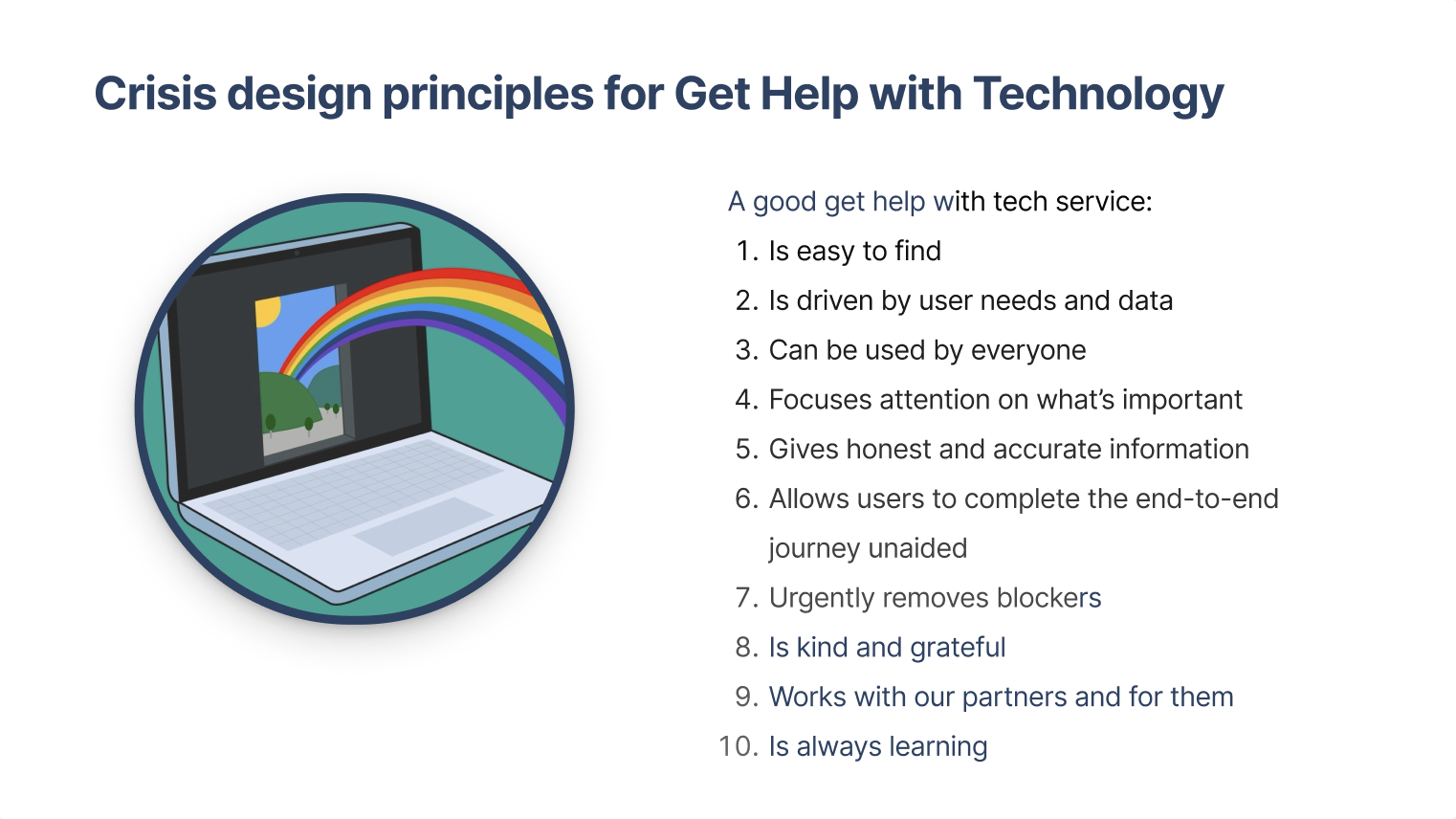

Crisis design principles I co-created with the programme teams through workshops and user feedback. We also took inspiration from principles for designing in a crisis and others.

Purposeful documentation

created high-level user profiles and user needs to inform prioritisation

created new, minimalist templates for discussion guides and reports

created high-quality documentation explaining key findings and decisions

Challenges

Unprecedented uncertainty

Schools need a lot of planning to run smoothly; in contrast, the pandemic brought unprecedented uncertainty.

On Wednesday 18 March 2020, school closures were announced. By the following Monday, all education had moved online.

Competing priorities

During the pandemic, the focus was on saving lives, reducing the spread of the virus and preventing health services from getting overwhelmed. The necessary reduction in social contact soon proved to be damaging to children, their learning and mental and even physical wellbeing.

Whose need is greatest?

Free school meals (FSM) and pupil premium (PP) are the proxy measures for economic hardship in schools. However, for the purposes of distributing laptops and connectivity to children, this measure was imprecise for a variety of reasons.

As the world shut down, people lost income overnight - this was not yet reflected in the figures. A family with 4 children suddenly needed 4 laptops, one for each child, on top of the adults needing laptops to access work.

The demand for laptops throughout the project continued to be a “moveable feast“, as one user described it.

Result

Delivering nearly 2 million laptops

Get Help with Tech programme delivered 200,000 laptops by June 2020. We scaled this to 1.3 million by the spring 2021, meeting the needs of many, many schools and families.

Beyond this, the programme went on to deliver nearly 2 million laptops and tablets.

Mission patches created by our designers to celebrate important milestones: 200,000 devices delivered in June 2020 and 1,000,000 in May 2021.

Shaping policy

User research helped inform some important policy, procurement and design decisions. For example we:

moved the ordering of devices from local authorities to schools

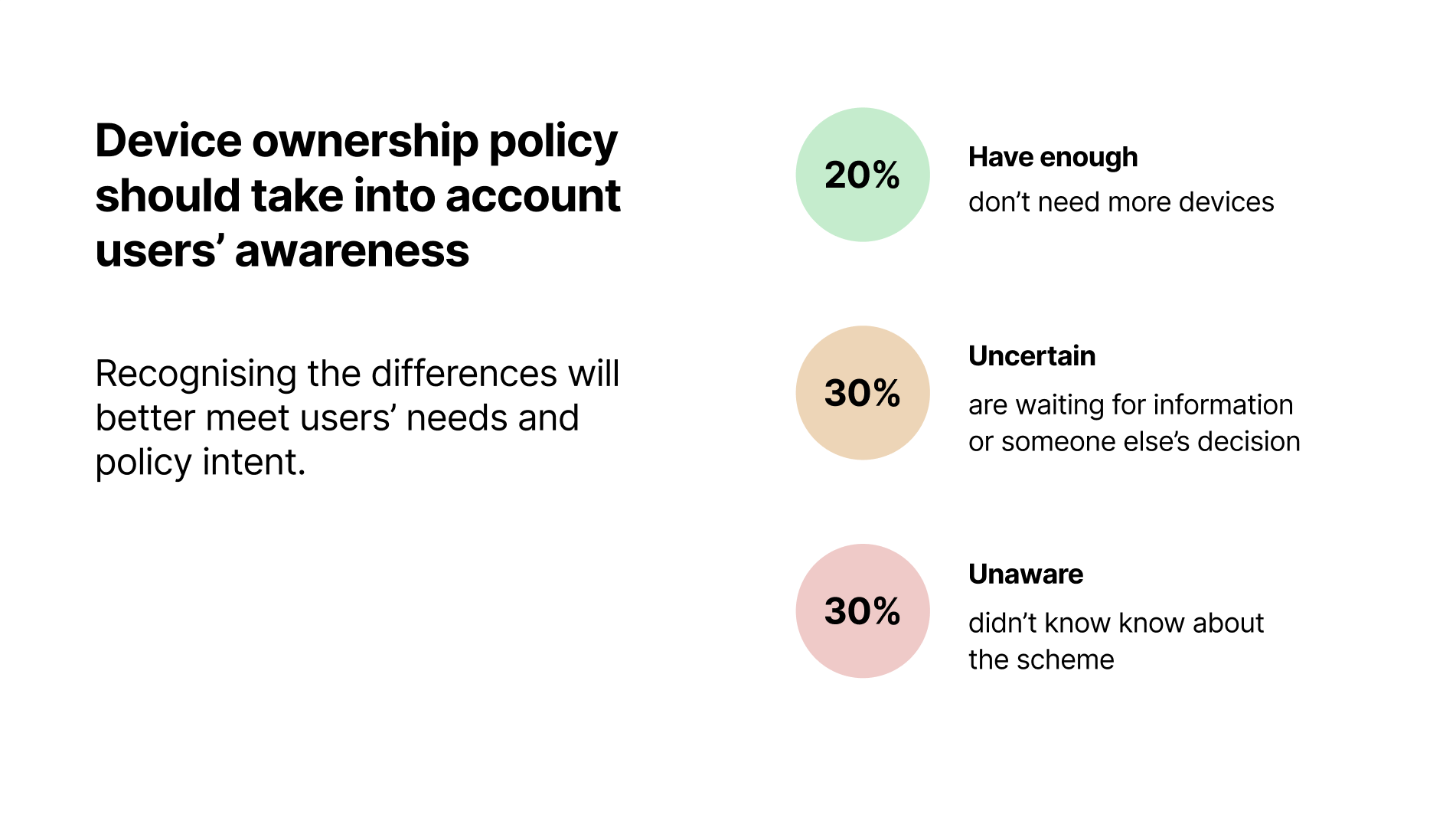

amended device ownership policy

ended a number of internet connectivity schemes that were proving ineffective

joined up key information across different suppliers - from ordering to administration of devices

offered a wider range of devices and setups - based on schools’ preferences

An example of how user insight could inform policy

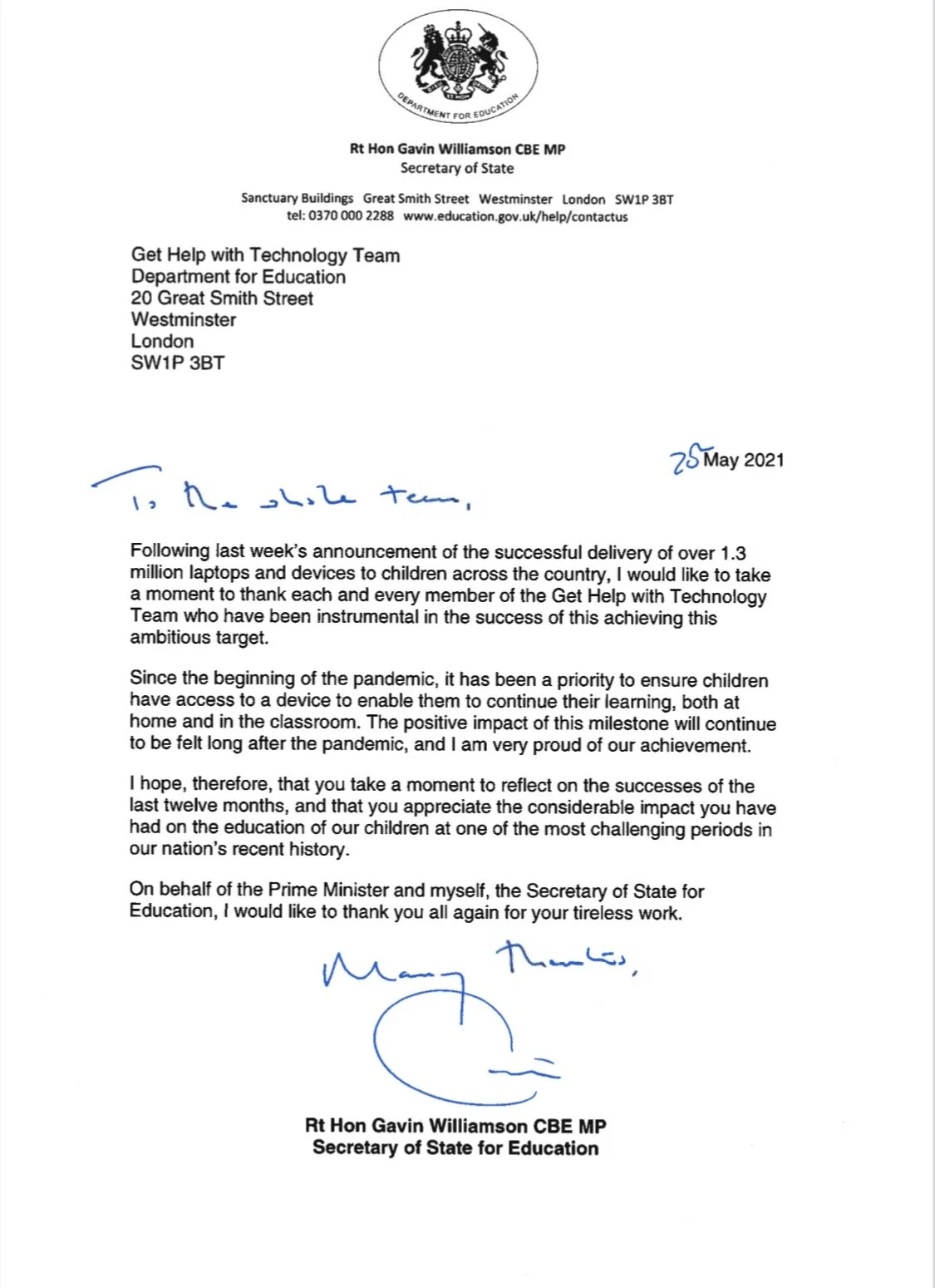

Recognition by the Prime Minister

Our work was recognised by the Prime Minister and the Secretary of State for Education. They acknowledged the programme’s “considerable impact” during “one of the most challenging periods in [the] nation’s recent history”.

A thank you letter sent on behalf of the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, written and signed by the Secretary of State for Education Gavin Williamson.

Passing GDS assessment

I led the user research section of the GDS assessment (known as peer review at the time and tailored to rapid pandemic programmes), which we passed with observations. I synthesised insights from hundreds of user interviews to describe the evolution of our users and their needs needs and how our research informed design and policy decisions.

“I think you did really, really well, you’ve probably done something in a couple of months that would have taken a year to plan and deliver”

Adapting our ways of working

There was no manual for working in a crisis. As a highly-experienced practitioner, I knew the frameworks well, but I had to create new, slimmed-down ways of working.

We often joked that we were ‘delivering a beta while in discovery’, meaning we were learning about the needs at the same time as building for them.

Transition to rolling user research

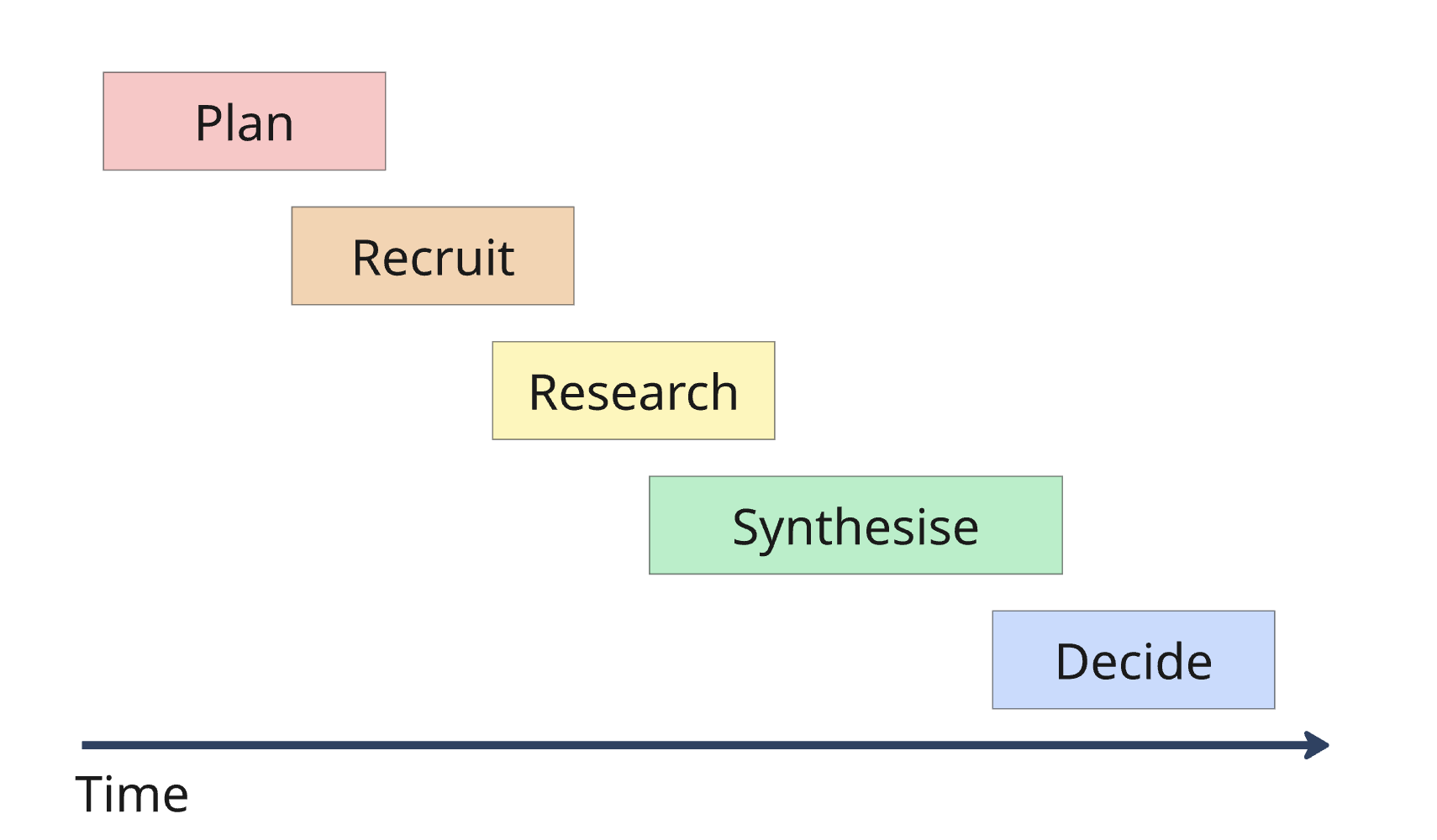

We scrapped the usual planning, recruitment, research and synthesis stages in favour of rolling user research and continuous design. Each week, we spoke to teachers and school leaders and made design changes. If we wanted research to inform policy decisions, we had to work fast.

Instant reporting

Synthesis and analysis often felt like a luxury because of the speed with which findings went out of date.

So instead I:

invited policy and design colleagues to take part in the research

joined meetings where decisions were made

reported findings instantly in Slack

did write-ups weekly and during quieter periods

A typical user research project follows distinct stages from planning to deciding what the findings mean for the design.

The pressure to ship working code fast made us adopt rolling user research where all activities were done in smaller chunks.

Building relationships with teachers and policy colleagues

The key thing that allowed us to work fast was building trusting relationships. We shifted our focus away from documentation and processes and towards creating understanding and rapport. This helped us recruit schools quicker and speak to them on a rolling basis.

Qualitative user research faster than quantitative data

Rolling user research was incredibly quick at picking up insights. We heard how schools were adapting in real time, while data took weeks to gather, analyse and share officially. This created a sense that user research could see into the future and allowed us to make better near-time design changes.

Final thoughts

Leading research during a national emergency wasn't just about speed, it was about quality under constraint. It helped me create a crisis toolkit. The approaches I developed - rapid research cycles, stakeholder immersion and network-based influence now form the foundation of my practice in environments where speed and clarity are competitive advantages.

If you’d like to hear more about this, or other work, let’s talk.